A Detailed Look at the Outcomes of Minneapolis’ Housing Reforms

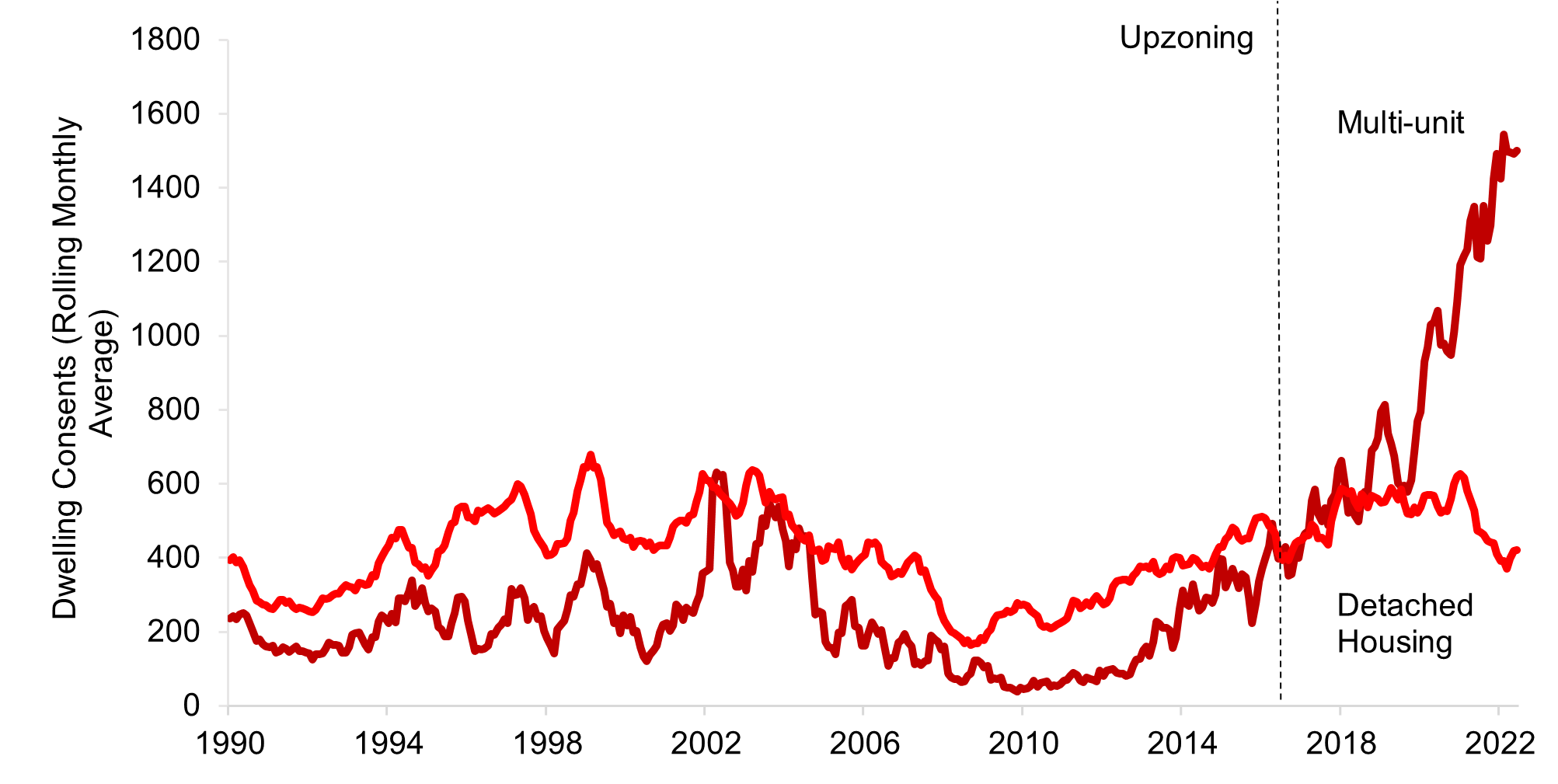

It is becoming increasingly clear from a growing body of international evidence that zoning reform can increase housing supply and lower rents. Auckland has received significant attention in recent years for its’ successful upzoning initiatives. California has also made news for its’ Builder’s Remedy, which may lead to a huge intake of new dwellings, although the impacts of this are still early and somewhat unclear. In part, the attention on these examples reflects their simplicity and communicability - a chart like the one below is quite effective at selling the power of zoning reforms.

While these examples are impressive, we need more proof across diverse locations to improve the case for zoning reform. An increased breadth of evidence not only improves the external validity of its’ effects, but also gives a clearer understanding of the relative effectiveness of different policies across different cities and urban areas. Plus, it makes it harder for anyone to simply brush off results or say they're just due to one-of-a-kind local factors.

With this in mind, I’ve been following the impacts of supply reforms in other locations for a while now. One of the most notable reforms in recent years was the Minneapolis 2040 plan, announced in 2018 and implemented from the start of 2020, which made headlines as it meant Minneapolis became the first city in the U.S. to abolish single-family-zoning, allowing triplexes to be built on most blocks. The Plan also included several provisions related to denser housing, including abolishing parking requirements and upzoning transit corridors. It quickly made waves around the world of housing policy, with NIMBYs and environmental groups expressing concern about the death of suburbia, and some YIMBYs quickly trying to draw a simple link between the reform and an increase in housing supply.

It has now been three years since the implementation of the 2040 plan, so it’s a good time to examine the evidence base and assess its impacts against expectations. On net, I believe Minneapolis adds to the growing evidence base that zoning, and supply-side reforms more generally, increase housing supply and improve affordability. However, as others have correctly pointed out, the results in Minneapolis have turned out to be far more nuanced, and interesting, than either side anticipated.

The challenges of evaluating supply reform in Minneapolis

At a high-level, Minneapolis has been very effective at building housing over the past decade, leading major American Midwestern cities in housing construction per capita over the last five years. This is in spite of a slower population growth (around 1% since 2017) than the other high supply cities such as Columbus and Omaha (both have grown around 2%). Clearly, Minneapolis is doing something right to build homes.

While it may be tempting to attribute this solely to supply-side reforms, there are several complex factors affecting the Minneapolis environment before and after the 2040 Plan’s implementation which make assessing the policy’s impact challenging. Unfortunately, we do not have access to sophisticated econometric research similar to that carried out in Auckland that can effectively control for these factors, isolate the plan's impact, and make specific policy effectiveness claims. As a result, we must consider these local factors when analysing time-series trends and correlations, in order to draw conclusions about the success of reforms.

Assessing the impact of the Minneapolis 2040 plan is challenging in part because of the exceptional housing supply in 2019, the year before its implementation. Most time-series analyses compare outcomes post-reform, to the year prior to reform - referred to as the ‘base year’. In that year, Minneapolis approved a record-breaking 4800 dwelling units, compared to an average of 3000 in the three years prior, and around 3400 in the three years since. If we ignore 2019, it’s clear that supply has increased somewhat post-Plan. But, if we were to use 2019 as our base year, we may (perhaps mistakenly) conclude that the 2040 plan decreased housing supply.

Analysing reforms implemented in an already recording-breaking market will inherently present methodological challenges - at least in the short run. At best, we may expect reforms to facilitate and maintain a longer boom in housing supply, which will only become identifiable over a longer time frame as we would expect the city to facilitate a greater level of density, a greater housing stock per capita, and lower housing costs, than comparable cities. But this is not something we can make strong claims about just a few years after reform. Minneapolis is unlike Auckland which had dwelling consents around the historical average at the time of upzoning.

Complicating matters further, we have two reasons to believe that the high supply prior to the plan's implementation was a result of relaxed housing supply restrictions.

First, the city had already undergone some housing supply reforms in the previous decade, the most significant being the reduction of parking minimums, first in 2009, and then again in 2015. They also relaxed Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) restrictions over the same period. (The 2040 plan further eased ADU regulations, and entirely eliminated mandatory parking minimums.)

The impact of parking minimums on housing supply is not well understood, but it is recognized that they increase construction costs and decrease the amount of land available for housing. Further research is needed, but it's reasonable to suggest that the reduced parking minimums in Minneapolis helped boost housing supply in the late 2010s. Experts familiar with the local market argue that parking reforms made a "significant difference" to supply. The data supports this, as the amount of parking required per dwelling unit steadily decreased in phases, first in 2015 after reforms, and again after the 2040 plan went into effect in 2020. While a few less parking spots per dwelling may not seem significant, it can add up in larger apartment buildings with multiple units. When assessing the impact of supply-reforms in Minneapolis, we should not just account for the 2040 Plan, but broader reforms occurring around it.

Secondly, the adoption of zoning reforms is contingent on a pro-housing government, which means they are more likely to occur in areas with a relaxed approach to existing laws. Typically, when a government aims to increase housing supply, they may first modify the way existing regulations are applied, a process that can be accomplished quickly, before enacting legislation to change the regulations themselves, which may take some time. The fact that the Minneapolis 2040 Plan was approved in 2018 but not implemented until 2020 raises the possibility that enforcement of existing restrictions was eased in 2018 and 2019. (However, it is also possible that there is a countervailing effect. In theory, some developers may have opted to wait until the new laws took effect to build under more favourable conditions.)

Additionally, we have reasons to believe that the 2040 Plan has faced some challenges that may have limited its impact once it was implemented. It was not fully enforced in until 2022, as some of its provisions were phased in the two years following it’s implementation. To make matters more complicated, the plan was temporarily halted in the middle of last year due to complaints from environmental groups, before it was allowed to proceed a few months later. These delays may have slowed down the adoption of the reforms and hindered their effectiveness.

Furthermore, the implementation of the 2040 plan coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and the social unrest that followed the murder of George Floyd in the city. These events may have contributed to a decrease in construction activity, as evidenced by a temporary decline in dwelling permits during the latter months of 2020. Supply has now returned to the peak of 2019 levels.

All of these factors make it challenging to determine precisely how much supply-side reforms have contributed to Minneapolis leading the Midwest in new housing supply for 5 years in a row. To some extent, it is a matter of personal judgment and prior beliefs about housing markets. However, it is worth noting that, besides these reforms, there is nothing unique about Minneapolis that can explain its higher rate of supply. The city has not experienced exceptional population or economic growth; in fact, it has mostly trailed comparable cities. It has not had particularly favourable local construction market conditions, nor has it seen significant or unique changes to tax policy. And yet it continues to build at a rapid pace - consenting to over 600 new dwellings in January of this year.

Has the abolition of single-family zoning increased supply?

Against these complex considerations, let's now turn our attention to the impact of the 2040 plan's most prominent feature, the elimination of single-family zoning.

The outcomes have been steady. The construction of ‘plexes’ (defined as 2, 3, and 4 unit structures) has experienced substantial growth in recent years, with a noticeable uptick starting from 2018, when the 2040 plan was first announced but not yet enacted, and have increased further after the policy’s full implementation. Over half of plexes constructed would not have been possible prior to the 2040 plan. As awareness of the plan spreads throughout the city and legal challenges are resolved, it is possible that this growth may continue in the coming years.

However, some consternation regarding the 2040 Plan becomes apparent when you look at the Y axis of the above chart. The complete data for 2022 show that Minneapolis approved just 63 plexes, while the city approved over 3600 total dwellings that year, meaning plexes made up less than 2% of total consents. This is hardly the surge we saw in Auckland.

The low level of plex construction has been a source of contention. Some have argued that further reforms may be necessary to drive construction, while others may argue that this is proof that zoning reform is ineffective.

However, the issue is perhaps not with the plan itself but with expectations. Historically, the majority of housing consents in Minneapolis have been for buildings with 5 or more units, and the city has not seen substantial single-family construction for decades. This is the opposite of the case of Auckland, where multi-unit lagged single-unit construction for basically its entire history. The Auckland Unitary Plan gave developers and land owners the option to build denser units than was the norm in the market. This was not the case with the triplex provision in the 2040 Plan. It was unrealistic to expect that plex construction would jump from 1% of the market to a far greater proportion.

Does this make the Plan a failure? No. For 2 reasons.

The first reason is that although plex construction represents a small proportion of supply, it is growing - up 40% since 2019, and 480% since 2015, and appears to be replacing single-family development. While single-family development collapsed during the COVID pandemic, plexes held steady. The 2040 plan likely supported this.

The impact of the 2040 Plan on plexes was also highlighted in a recent paper, which showed that the market valued the option to build denser development on single-family blocks. Blocks within the Minneapolis city border increased in value after the reform, relative to those just outside. And, larger blocks with more space available increased relatively more. This effect was also observed in Auckland, and suggests that zoning regulations were indeed having an impact on the market. Over the long run, plexes may continually make up a small, but non-trivial, component of housing supply, and compound into thousands more dwellings being built than would have otherwise existed.

The second reason is that the 2040 Plan was much more than single-family zoning abolition. It included the upzoning of transit corridors, the setting of minimum height limits in densely populated areas, and the elimination of maximum occupancy caps. In fact, in 2021, Minneapolis rejected an 8-story development for being too short, requiring it to be re-proposed at 10 stories, in stark contrast to other zoning systems which often force buildings to be shorter.

Some local experts believe that these broader reforms are more significant than the abolition of single-family zoning, due to Minneapolis’s urban makeup. They also argue that single-family zoning abolition soaked up much of the media attention devoted to the plan, and allowed these other reforms to be implemented under less scrutiny.

Given that almost all new housing in Minneapolis consists of dwellings with 5 or more units, it’s not hard to believe that reforms which facilitate denser development have helped maintain Minneapolis’ high-rate of dense supply (including the parking reforms prior to the Plan’s implementation). In fact, it's possible that the Plan is working precisely as intended, providing more ammunition for the already-active dense housing market to continue building at a high rate, while steadily supporting a growing plex market.

Has high supply seen lower rents?

Regardless of the reasons why, it’s clear that Minneapolis has built a lot of housing over the past decade. Even if you don’t buy that the reforms discussed above are responsible for a significant proportion of this high supply over the past few years, it's worth examining whether this increased supply has led to improved affordability. Note the the claim that zoning reform will result in higher supply is independent of the claim that high supply with improve affordability. Critics of YIMBYism frequently challenge both of these assertions with separate arguments. Some, for instance argue that the market will never build enough housing to supress rents over the longer term. This contradicts the evidence from Minneapolis.

Minneapolis rents have declined in nominal terms since 2017. Most other Midwestern cities have seen rents increase over 30% over this period. Remember from earlier that these cities have built much less housing than Minneapolis. The only other city in a similar ballpark is Milwaukee, which has had a declining population, and still has had rental growth of over 10%. Rents in Minneapolis largely held steady, and began to decline around 2021, which is 2 years after the record breaking year for consents in 2019. I’ve already written how in housing markets consents can lag completions by around 2 years.

The fact that nominal rents declined over this period was quite surprising, so I checked with other data sources and they all more or less tell the same story. It’s become much cheaper to rent in Minneapolis over the past few years, particularly when you consider rising incomes and consumer prices generally.

Other indicators also reveal improving affordability. The Minneapolis Fed shows that rental growth has been slower than income growth for renters, and the proportion of housing burdened households (those spending more than 30% of their rent on housing) has fallen. Some more microdata household level analysis is needed to make further inferences on the distribution of impacts however. And, given high inflation and high housing supply over the back half of 2022, it’s not unreasonable to expect housing as a proportion of household budgets will decline further.

Others have noted how homelessness is correlated to housing affordability. While it is tricky to make strong claims, it is worth highlighting that homelessness in Minneapolis has declined over this period. This is in spite of the fact that across Minnesota at large homelessness has increased. The timing of the homelessness decline also corresponds to the period of falling rents from 2020. More data will be released soon for 2023, and it will be interesting to see if this trend continues.

Conclusion

So what can we conclude from the experience of Minneapolis?

First, jursdictions that facilitate more supply often see much lower housing costs and rents. It’s also worth noting that, much like Auckland, the fundamentals for housing construction in Minneapolis at the moment are not strong. Construction costs and inflation are high, supply chains have been disrupted, and interest rates are rising. The high levels of supply have been achieved in spite of this. Had the 2040 Plan been implemented earlier, it’s possible the effect on supply could have been more discernible.

Second, single-family zoning abolition may not be the sole solution for increasing housing supply in areas where multi-unit developments and apartment construction are already prevalent. Reforms such as eliminating parking minimums and facilitating transit-oriented development may be more important. We should recognise that housing markets are different - Auckland’s reforms would likely work in Australian cities, for instance, due to similar urban composition, while Minneapolis’s reforms may work in other major American cities.

Likewise, the level of government implementing reforms may matter. Perhaps city governments in the U.S., with higher rates of dense development under the status quo, should focus on facilitating density around transit, while State governments focus on single-family zoning abolition - as reforms will apply in broader suburban and exurban areas. For this reason, it will be interesting to see how statewide reforms in Maine will perform as they come into force later this year.

Third, we also need much more research on the impact of the broad suite of potential housing reforms - including transit-orientated upzoning, parking reform, and ADU construction. These reforms are much less controversial than blanket upzoning, and will likely face less community resistance. Indeed, around a dozen jurisdictions globally have abolished or significantly reduced parking minimums over the past few years, and many others will likely follow. If it can be proven that these reforms can be effective in increasing housing supply, it may be a quick and effective path forward to improving housing affordability.

Finally, we need more sophisticated research into the reforms in Minneapolis that is able to accurately identify the proportion of new supply attributable to the various reforms over the past decade. Minneapolis seems like an environment ripe for econometric work that attempts to causally identify the impacts of parking minimum reform, transit corridor upzoning, and ADU reform, on housing supply.

Overall, Minneapolis’s experience with housing supply reforms is a complex one, and one that requires a reasonably sophisticated understanding of local factors to understand. But, at the end of the day, the conclusion is simple: the city has found a way to build a lot of housing in recent years, and affordability has improved considerably as a result.