Auckland

Background

Since 2010, Auckland has been governed by a unified entity, the Auckland City Council, a result of the consolidation of multiple local governments into one. In November 2016, Auckland upzoned approximately three-quarters of its residential land area by abolishing single-family zoning, under the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP). The AUP was in the works for many years before – a draft was published in 2013 – which gave developers time to observe the new regulations and commence planning prior to the policy becoming operational. Developers were allowed early access to the AUP in Special Housing Areas (SpHas) from 2013 provided they provided an amount of affordable housing in their developments (similar to an inclusionary zoning policy). This means that upzoning impacted supply in some form from 2013. More information on the institutional background can be found here.

The Impact on Supply

The AUP was associated with a large increase in new dwelling starts, predominantly comprising multi-unit dwellings. Some of the increase reflects dwelling consents that would have occurred regardless without the policy change and therefore cannot be causally ascribed to upzoning. However, we have two papers that undertake sophisticated causal analysis to analyse policy impacts:

Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips 2023 compares areas that were upzoned in Auckland to areas that were not upzoned to generate a counterfactual of what could have occurred in the absence of the policy. The difference between upzoned and non-upzoned areas can be seen below (Greenaway-McGrevy and Jones 2023, below right figure). However, some construction activity was likely moved from non-upzoned to upzoned areas due to the policy. The paper estimates how large these ‘spillovers’ would have to have been between areas for the policy to not have a statistically significant effect on housing construction. The paper finds that the rate of housing construction growth would have to have increased fourfold in the absence of the AUP for the policy to have had no impact. Point estimates suggest that the policy added 20 000 additional new dwellings over a five year period. This represents just over 4 per cent of the stock of housing in the Auckland region in just five years. This is strong evidence that upzoning reforms can be fast at delivering on new houses.

Greenaway-McGrevy 2023 compares Auckland to other urban areas within New Zealand to generate a counterfactual of what could have occurred in the absence of the policy. It does so using a “synthetic control method”. Over the six years after the AUP, new housing starts issued exceed those of the synthetic control by approximately 43,500 – forty five percent of the 97,000 permits issued in Auckland since 2016.

The latter paper finds a larger impact of the policy as it makes less conservative assumptions about housing supply growth.

The Impact on Prices and Rents

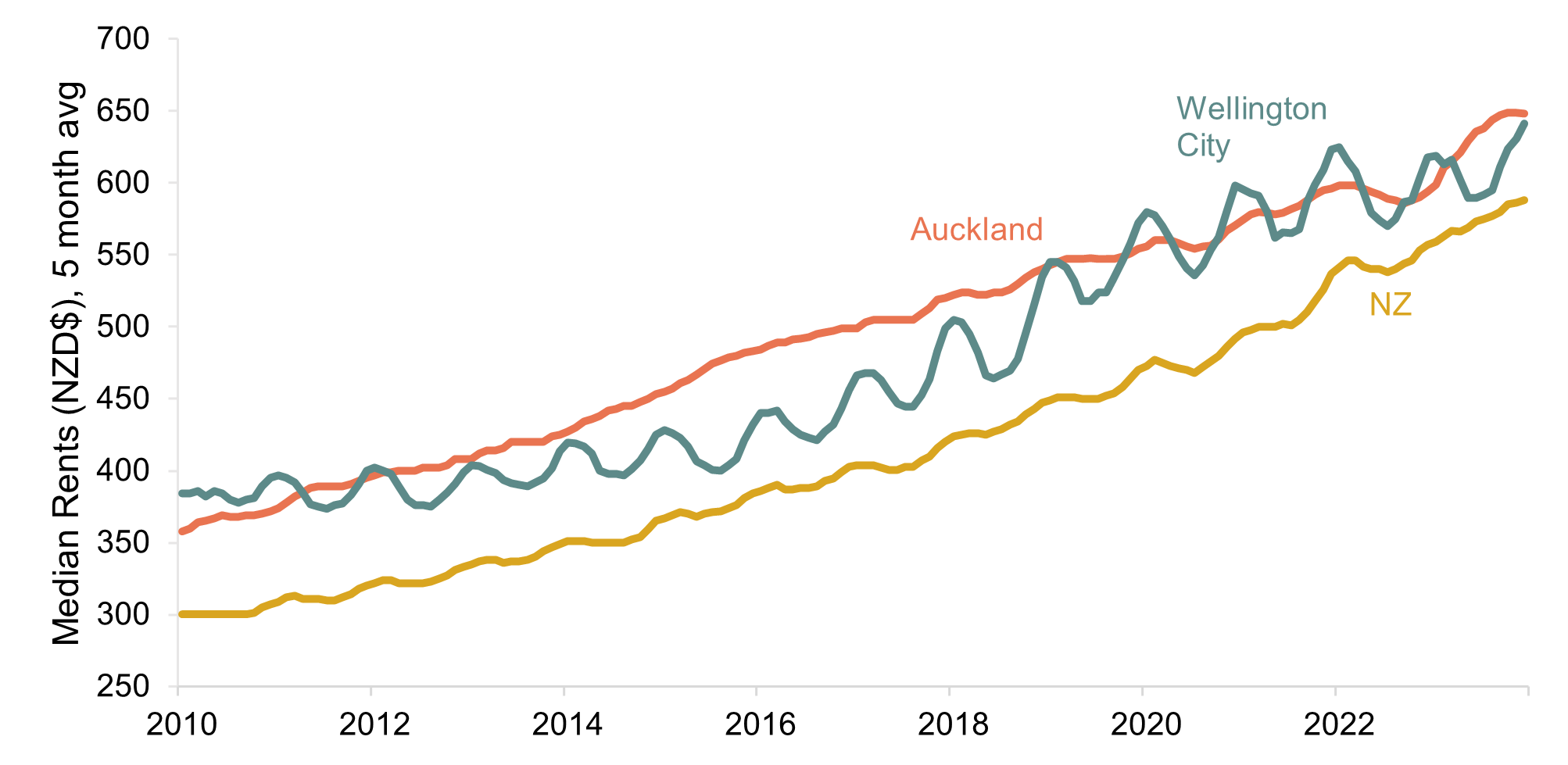

In 2010 Auckland was the most expensive major city in New Zealand to rent in, with renters having to pay a ‘premium’ to rent there relative to other cities. Since the upzoning reforms, rents in Auckland have grown more slowly than the national average, as well as Wellington (another large major city for comparison): it is now cheaper, on average, to rent in Auckland than in Wellington.

A recent paper undertook the task of estimating the impact of upzoning on rental prices in Auckland. Utilizing a 'synthetic control' counterfactual approach, the authors concluded that rents are between 14-35% lower than what would have been anticipated without the implementation of upzoning reforms.

Moreover, rents in the lower quartile have risen more slowly in Auckland than the median rents. From 2010 to the end of 2016, lower-quartile rents saw a growth of approximately 38 percent. Yet, from 2016 until now, the growth in these rents has tapered to a mere 14 percent. It's worth noting that these comparisons could possibly understate the actual impact of upzoning on rental rates in Auckland. Lower rental costs in Auckland could potentially lure more people to move there from other cities, thereby shifting demand towards Auckland and away from other regions. In response, landlords in other parts of New Zealand may find themselves having to reduce their prices to stay competitive.

There is also some evidence that the rate of rental price growth is continuing to slow in Auckland. With a large amount of new supply in the pipeline the biggest price effects may still be yet to come.

But, the best metric of the policy impact of upzoning is the degree to which it has assisted housing affordability as measured by the rents as a share of household income. The results are promising:

Between 2016 and 2023, nominal household incomes rose by 47 per cent, while rents grew by just 29 per cent.

Median rent to median incomes have dropped substantially in Auckland, from 22.7 per cent in 2016 to 19.4 per cent in 2023. In contrast, New Zealand as a whole saw this ratio rise from 20.8 per cent to 22.5 per cent. (In other words, Auckland is now more affordable than the rest of the country on average for the median renter.)

The evidence on house prices is also promising although, unlike rents, they are sensitive to changes in interest rates than supply in the short-to-medium term. From the end of 2016 to February 2020, Auckland house prices had risen by only around 5 per cent. Then, a significant cut in interest rates then saw prices increase - but by less than the rest of the country. Rising interest rates have now seen prices begin to decline. The ultimate outcome: since 2016, Auckland's house prices have risen by roughly 20%, a stark contrast to the 65% increase seen in the rest of the country. This supports the theory that a more flexible housing supply dampens the impact of demand-side factors, such as interest rates, on prices.

It will be interesting to see if house prices in Auckland decline below 2016 levels at some point over the next decade (particularly if interest rates remain high).

Median Rents

Change since Upzoning

Nominal House Prices

Change Since Upzoning

Affordability

Real Rents

Other policy impacts

The Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP) has been so successful and well-received that it inspired the New Zealand government to implement further reforms. The 2020 National Policy Statement on Urban Development mandated large cities to zone for residential buildings within walking distance of rapid transit stations. Following this, the Medium Density Residential Standard was introduced, superseding local councils' regulations to permit three-story buildings with three dwellings on most residential parcels. Remarkably, these reforms received tri-partisan support.

However, these policies have been pledged to be abolished by the newly elected National Party in New Zealand. Only Lower Hutt has currently acted upon them, and it unclear whether other councils will do so, even if they are reversed by the Central Government of New Zealand.

For a detailed overview of these policies, refer to the upzoning tracker. It's estimated that these measures will add approximately 75,000 additional dwellings in the next five to eight years.

A cost benefit analysis of the proposal noted that the productivity benefits of such a policy are enormous:

If enacted in 2022, the net benefit of the upzoning accruing by 2043 “is estimated at $14.5 billion in 2019 dollars, or about $11,800 per 2022 household in added disposable income over 21 years. The total cumulative value of long-term distributional impacts over the same period is about $198 billion” (Emphasis added).

Auckland residents hold a positive view towards these transformations. After witnessing the benefits of an increased housing supply, less than a third of Aucklanders perceive the shift towards more dense housing as a negative development.

Sources/ Further Reading:

Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips (2023)

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2022/01/24/new-zealands-bipartisan-housing-reforms-offer-a-model-to-other-countries/

https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/red-tape-cut-boost-housing-supply

https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/Files/Medium-Density-Residential-Standards-A-guide-for-territorial-authorities-July-2022.pdf

Stats/Data Sources:

https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/building-consents-issued-july-2022/

https://www.tenancy.govt.nz/about-tenancy-services/data-and-statistics/rental-bond-data/

https://www.reinz.co.nz/residential-property-data-gallery