How to make housing affordable in Australia

It’s not news to anyone that Australia has a housing affordability problem. New articles pop up every day about poor Australians struggling to find affordable rental housing, or about young people unable to break into home ownership. You’ve probably seen all sorts of charts and data showing that prices have become detached from incomes, or that rental affordability has become increasingly tricky.

It may seem like affordable housing is a goal that is economically or politically impossible. As is the case across most of the developed world, Australian governments push poor policies and do not address the fundamental issues. Going into the last Federal election, both parties pushed policies that aimed to subsidise (already inflated) demand - attempting to support home ownership, and offered very little for renters. State and Local Governments also do very little to push for more housing supply, instead prioritising things like ‘neighbourhood character’ over making housing affordable.

This is perpetuated by the poor quality of research and discourse related to housing in Australia. Many would have us believe that the only way out is through fundamental reform of the system, or building hundreds of thousands of social houses - neither of which are very likely to ever occur. Research is pushed which has been debunked, and fundamentally misunderstands the market. NIMBYs fight against new development, inflating prices, while the media pushes narratives around AirBNB or empty dwellings.

This all seems quite bleak. And yet, fixing our housing problem is actually not that far out of reach. Few are aware that several cities overseas have already passed policies that have already made housing significantly more affordable, and others are following. These reforms are not particularly complicated, and we could easily copy many of them here to make housing much more affordable, lift our productivity, and lower our environmental impact.

What’s the problem?

The main reason why housing is unaffordable is that Australia does not build enough houses, and has highly inelastic housing supply. This means that when interest rates fall, or the population grows, prices and rents go up, rather than many more houses being built. The number of dwellings built has not kept up with demographic trends over the past two decades, meaning that housing has become relatively scarce - hence prices go up.

When commentators complain about changes in interest rates or migration increasing the price of housing, what they’re really commenting on is the fact that supply does not respond to the increase in new demand. New migrants or lower interest rates doesn’t cause the price of apples to balloon, for instance - we simply grow more. Likewise, the reason why housing has become commodified and a significant source for investment for many is because of it’s scarcity: investors can count on house prices going up simply because they know that demand will continue to grow at a faster rate that supply.

To combat this, the Australian community has to accept denser cities. This doesn’t mean skyscrapers everywhere - it means more townhouses and low-rise apartments, for instance. This can be a good thing. Denser cities can have more amenities - such as cafes, restaurants and entertainment - within walking distance, means less time spent in cars and in traffic, and can mean less destruction of the environment through urban sprawl.

Of course, as is the case in all developed countries, there are other important factors too - more supply is not the only solution. Many households have low incomes, or struggle with social issues like drug addiction or domestic violence. Even if we had hundreds of thousands of new dwellings, these households need government support to be able to afford housing.

So, let’s talk about some reforms that can shift the discourse and the state of housing policy in this country. But first, we need a quick framework of how to think about affordability.

A framework for thinking about affordability

People can mean many different things when they talk about ‘housing affordability’. The most common way appears to be referring to the affordability of home ownership, which has been dropping over much of the western world. People point to things like rising prices in nominal terms, income-to-price ratios, or the amount needed for a deposit. But, housing affordability could also be in reference to the rental market: many reports refer to ‘rental stress’ - defined as spending more than 30 per cent of one’s income on rent.

These definitions all are slightly different - notably, house prices are far more responsive to interest rates than rents are. But, at their core, they have one key similarity: they are always some function of costs and incomes.

While the housing market is incredibly complex, there is one core truth - if we can lower costs, or increase incomes, housing will become more affordable. This is the framework through which we should think about policies that proport to increase affordability: do they increase incomes, or do they decrease costs? If they do neither, we should toss them out - they are not getting at the core of the problem. There is some complexity where some policies may have countervailing effects - these should be deprioritised as well, relatively to others which are unambiguously good. For example:

Some policies may increase incomes (for some) but also increase costs (for example, first homeowner grants).

Some policies may lower costs, but decrease incomes (for example, restricting migration).

All policies below will either lower costs or increase incomes - plain and simple.

Reforms to lift incomes

For many households, even if we could lower the cost of housing significantly, they simply will not be able to afford reasonable housing. For some, social housing (publicly owned and subsided) is the best option. But others could be able to rent affordably in the private rental market if they had more money.

The main way that governments could do this would be through reforming the main income support program for low income households: Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA). As it stands, the program has not been reformed since the late 1990s - it has merely been indexed to CPI. Since then, rents have increased at a far higher rate, meaning that the purchasing power of CRA has significantly declined. This is in spite of numerous reviews indicating that the payment should be reviewed, reformed, or increased.

The program is also not well optimised. Around 2 in 5 recipients are still in rental stress, but this varies by recipient type. Younger people and those on allowances are far more likely to remain in rental stress, while those on Family Tax Benefit are not. There is likely merit to changing the structure of the payment to give relatively more to:

Those on allowances - including Youth Allowance and Jobseeker

Single person households - as households with multiple incomes are more easily able to find affordable housing. Essentially, renting a dwelling with an additional bedroom only has a small marginal cost for a dual-income household - a luxury singles do not have.

Some frown on CRA expansion, claiming that it is merely taxpayer funds flowing to landlords. This is false. CRA is an untied payment - meaning that it can be spent on anything, not just housing. And, even if CRA was spent entirely on rents, it would also only be a small proportion of expenditure in the private rental market. It is also well-targeted: lower-income households receive it, on average. People who oppose CRA therefore oppose general untied income support to people on low-incomes.

Relatedly, general income support programs should be reviewed. Almost all top economists agree that the current rate of JobSeeker (Australia’s unemployment benefit) is too low. Expanding the social safety net, and offering something like an Earned Income Tax credit, would go a long way to making housing affordable for low-income households.

Reforms to lower costs

Lowering the cost of housing is the main way that Australia could improve affordability. Unfortunately, Governments seem to have a huge focus on the demand-side, which does little to make housing more affordable. Supply-side policies make housing more affordable for everyone - unlike first home ownership grants, for instance, which benefits just those who receive it. And, all new housing lowers prices, not just housing targeted at low-income households. (If you’re interested in how this works, you can read more about the mechanisms of filtering and movement chains - I will also likely write more about them later).

Make no mistake: more supply guarantees lower prices and rents, all else equal. Anyone who claims otherwise does not understand basic economics.

1. Abolish Detached Housing Zoning

Australia constrains its’ supply of housing through zoning: in most areas, it is only legal to build detached housing. State governments do a poor job of publishing the proportion of residential land zoned by each category, but where data are available, it paints a bleak picture. In Canberra, around 81 per cent of all residential land is zoned for low density. Even in more populated areas - such as inner-urban Melbourne, nearly 30 per cent is zoned for low density. Furthermore, zoning policy is highly inequitable across Local Government Areas - Bayside City Council in Melbourne, for instance, has over 80 per cent of residential land zoned for low density, while poorer areas are picking up more of slack.

The end result of this is significantly higher housing costs and highly dispersed cities. Zoning raises house prices above marginal costs by 73 per cent in Sydney, 69 per cent in Melbourne, 42 per cent in Brisbane, and 54 per cent in Perth. Australian cities are amoung the least dense in the developed world. London is over twice as dense as Sydney, and four times as dense as Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide. Average commute times have been growing significantly over time.

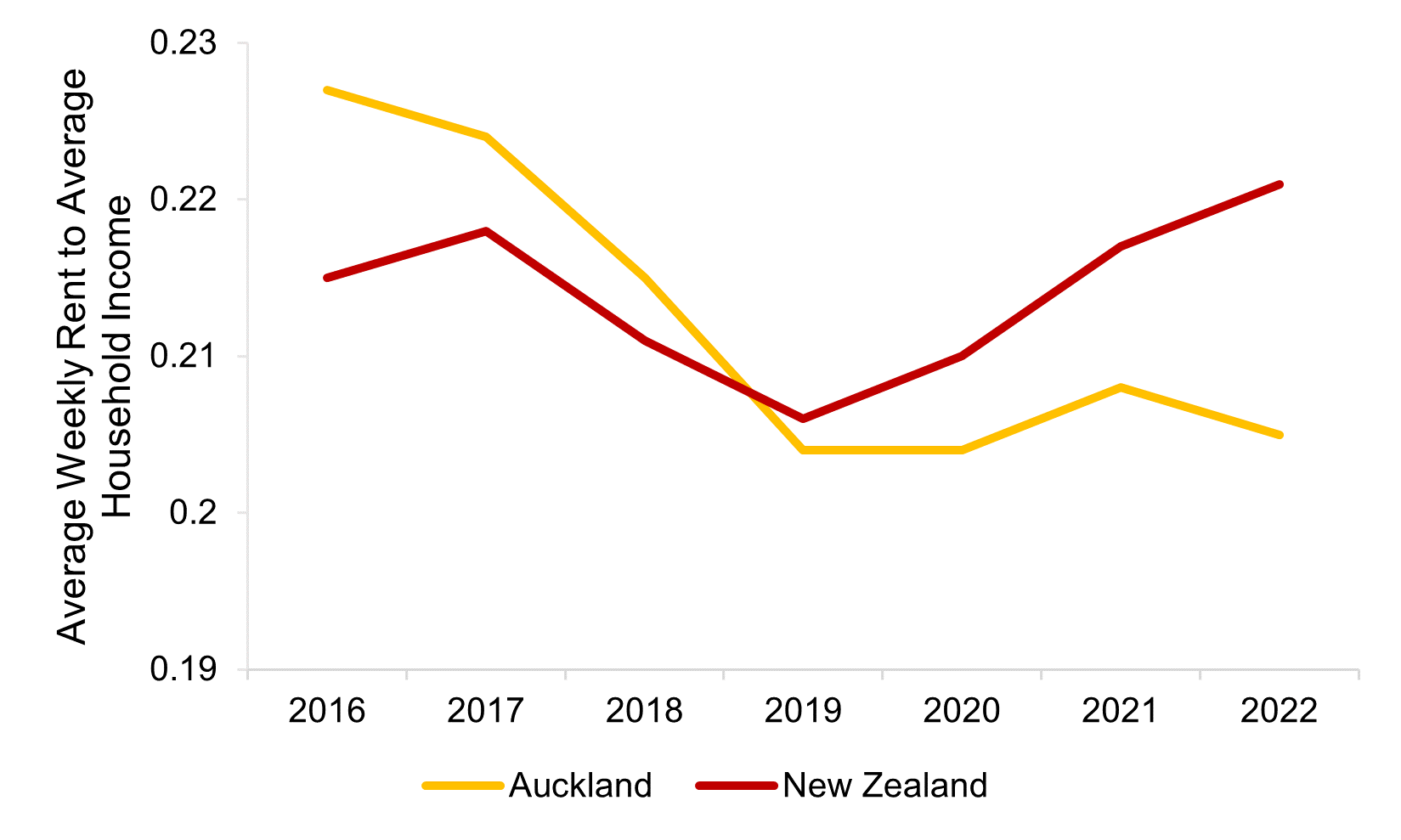

Abolishing zoning that only allows for detached housing - at least in inner-urban areas - to allow for more medium density, would likely lead to an enormous increase in housing supply, and significantly lower housing costs. Auckland - which has a similar population density and urban structure to Australian cities - recently allowed medium density across three quarters of its residential land, and has seen significantly more new housing built. Rents and house prices have since grown more slowly than other cities, and in recent months have even started to decline. Indeed, affordability across the city has increased: the median Aucklander is spending 20 per cent of their income on rent, down from over 22 per cent in 2016. The rest of the country has gone in the opposite direction.

Even if Australian cities adopting this reform only led to a supply response half as large as what occurred in Auckland - say 2 per cent - a model of Australia’s housing market predicts that this could lower rents and house prices by around 5 per cent in just a few years. Given that zoning restricts supply more in Sydney and Melbourne than in Auckland (this paper uses the same technique as the paper above, and finds zoning inflates costs by 56 per cent above marginal costs in Auckland), the effects on supply from zoning reform in Australia could be even larger than in Auckland. A reform slightly larger than what has already occurred in Auckland (a 5 per cent increase in supply) would lower house prices and rents by around 12.5 per cent.

Such a policy could even be popular. A plurality of Aucklanders feel positively about recent changes to allow for more density. The Australian community also appears to feel more positively, or at least neutral, towards medium density. A 2017 survey by the ACT planning department found that only around 10 per cent of Canberrans wanted less townhouses and duplexes in their neighbourhood, and just 30 per cent wanted less units of up to 2 storeys. A survey of Sydneysiders found that while 14 per cent of Sydney’s housing stock was semi-detached or townhouses, the community would prefer this proportion to be 25 per cent. This is certainly politically feasible.

Nor is this policy particularly radical. At least 7 jurisdictions globally have abolished detached housing zoning since 2016, and this number is only likely to increase over the next few years. Where this has been tried, it hasn’t destroyed neighbourhood character either: new dwellings can look nice and fit in with existing ones. Australia is at risk of falling behind the rest of the developed world if this policy is not pursued more vigorously. A simple change to change low-density zoning to allow three units up to three stories (‘3 by 3’) on most blocks would bring us from behind the curve to the forefront of world.

State governments could accomplish this by setting zoning ‘budgets’ for local governments, which outlines the maximum that each local government area can zone for detached housing. This proportion could increase the further away the local government area is from urban hubs. For example, local governments within 5kms of major urban hubs could be banned from zoning for low-density, while local governments 15kms away could be restricted to only zoning 25 per cent of their residential land for low-density. This would allow local governments some flexibility in where they upzone, but would result in more fairness across local areas.

2. Upzone Transit Corridors

Allowing medium density on most residential blocks should be supported by facilitating higher density around transport infrastructure. The advantage of building densely around transit (such as train and tram lines, and major bus routes) is obvious, as it overcomes the need to build more infrastructure to deal with issues such as congestion. As residents will use the transport infrastructure heavily, this will also spur State Governments to invest more heavily in services and service quality, to make a better city for everybody. Commercial buildings - such as restaurants and cafes - can be located nearby to create vibrant, walkable communities.

Other jurisdictions globally have upzoned transit corridors to great success. Minneapolis bucked the norm in zoning systems by setting minimum, not maximum, height limits around transit corridors - in 2021 a building in was actually rejected for being too low, and had to be re-proposed with 2 extra stories. New Zealand’s recent National Policy Statement on Urban Development committed to upzoning land to allow for up to six stories within walking distance of urban transport.

Sydney and Melbourne both have already eased zoning restrictions somewhat within walking distance of train stations. But, there is scope to go much, much further. Research estimates that denser development around urban train, tram, and bus routes in Melbourne could accommodate between 1 million to 2.5 million extra people, at an average density of between 200 and 400 people per hectare, primarily through 4 to 8 storey buildings. (Hong Kong has around 380 people per hectare on average across the whole city, for a comparative.) The Property Council of Australia estimates that there could be a large capacity to upzone similar areas in Perth, at a density of between 60 and 160 people per hectare.

State governments allowing high density within 500 metres of major transit hubs would lower the cost of housing significantly, and would lead to more vibrant, walkable cities.

3. Abolish Car Parking Minimums

Minimum parking requirements are prevalent in Australian zoning and land use regulation. In Sydney, the Apartment Design Guide leaves it up to Councils to determine minimum car parking requirements, for instance (unless it is within 800 metres of train or light rail). The rationale for minimum off-street car parking is to manage spill overs to on-street parking, which can contribute to congestion. But, there are likely better ways to target this - regulating street parking directly, for example.

Minimum parking requirements may seem like small-fish when it comes to housing supply and affordability. But, providing off-street parking to residents can be hugely expensive, and results in scarce land being used for cars, not people. The Austroads’ Guide to Traffic Management estimates that land and construction costs of off-street parking spaces can vary between $50 000 and $80 000. Forcing developers to include off-street parking can therefore potentially add hundreds of thousands of dollars to costs of building.

The NSW Productivity Commission estimate that the cost of building excessive parking in Greater Sydney is $264 million. While others find that that the Victorian Planning Provisions for minimum car park requirements have resulted in an over supply of parking spaces in residential apartments.

Minneapolis has gradually relaxed minimum car parking requirements over the past decade, and has seen the average number of spaces provided almost cut in half, cutting development costs significantly. It is no surprise that this has been associated with a significant increase in dense housing supply, and lower rents. Since Buffalo removed parking minimums, half of new developments have used less car parking than previously permissible. Half a dozen or so local governments in the U.S. have abolished minimum parking requirements entirely: Australian cities should follow.

Parking per dwelling in Minneapolis

4. Relax restrictions on secondary dwellings and minimum floor spaces

These two reforms can be lumped together, as they both relate to the ability to build, and live in, smaller dwellings. Secondary dwellings - for instance granny flats - can be built in backyards without a need to demolish the main dwelling, and can be rented out to lower-income households (for example students). Minimum floor spaces restrict the ability of developers to provide diverse housing to meet the needs to households.

Some are squeamish about relaxing these restrictions, claiming that smaller dwellings embody the failure of the market to provide affordable housing, and would result in an even lower quality of life to low-income households. For example, an article about a 7 square metre ‘microflat’ in London went viral earlier this year, with many deriding it as an example of how the market is imbalanced in favour of landlords. But, the article itself highlighted the merit of these policies, mentioning that: “The current tenant lives elsewhere for most of the time and spends just a night or two each week in the flat as it is closer to work.” It seems like the apartment was not a story of low-income people being exploited, and was rather an example of how innovative housing models can be a good deal for everyone.

Secondary dwellings and small apartments can be provided cheaply, and can allow for more dwellings per unit of land. They can be a good option for many households that do not require a large amount of space - for example students, frequent work travellers, and singles. Students on Youth Allowance and AusStudy are very likely to be in rental stress, under the status quo, for instance, but may expect higher lifetime incomes post-study. Many would likely accept a small dwelling for their few years of study to live closer to campus or transit. Most households can look at the size and amenities of a dwelling and make a trade off between the rent they would save, and the liveability of a dwelling.

The NSW Productivity Commission estimate the benefits of removing minimum apartment floor sizes to equal around $1 billion in NPV terms.

That said, these restrictions being relaxed should be supported by other policies. Construction regulations may need to be more strictly enforced to ensure that these dwellings are safe. Zoning restrictions more broadly need to be relaxed to not ensure that that rental market conditions are loose, and that landlords do not have exploitative bargaining power. But, provided these dwellings can be provided safely, they would represent a meaningful low-cost option for many households.

Other reforms may help, but are smaller fish

Reforms to incomes and rents are the main way that governments could improve housing affordability. But, there are likely a few other policies that are worth considering - their impacts are small, but will take us in the right direction.

Tax reform - for example removing the capital gains tax exemption, negative gearing, the aged pension test exemption, and reforming stamp duty, would likely lower house prices somewhat. They will also likely be more equitable, and allow us to treat asset classes more neutrally. But, empirical estimates of their effects are small - usually in the range of 3-5 per cent. This is better than nothing, but is not as important as supply reform.

Building more social housing - an additional unit of social housing is probably on-net good for Australia. But, many confuse the fact that the demand for social housing outstrips supply as evidence that we need hundreds of thousands of new units. Demand for social housing is inflated by poor conditions in the private rental market - lowering rents through supply reform will mean that less people will need it.

Conclusion

Housing affordability is not rocket science - it is a function of incomes and prices. We need to give low-income households more purchasing power, and build more houses to lower costs. Reforms to achieve this are simple, and many of them have been proven overseas. The time for debate is over - we need action, else Australia will fall further behind the rest of the world.